How to Run a Game (Part 23...Kind of) - Building a community

Quite a few of my students have found this blog, and they've been asking me to write about key members of the various groups I've been running. They've also been trying to work out who is who among the various nom-de-plumes already included in various articles. That's been kind of nice, and it basically leads into a lot of the things that I've been discussing.

I've always thought that one of the aims when running a good game, is creating an event that people want to come back to. Anything that might help that situation is potentially a good thing. If I can get people talking about the game between sessions, this is a good thing (as long as the game doesn't become detrimental to other parts of their life... and I've seen that happen in the past, briefly mentioning "Mephisto" from the distant past at the end of part 7). If I can get players more immersed in the events of the story while the game is happening, that's a good thing. If I'm listening to what my players want, and collaborating with them to create something shared and special, this is a good thing. If I can get players wanting their friends to join in on the experience, that's a good thing...up to a point. If I'm losing the interest of the core players because I'm trying to cater to the new arrivals rather than sharing the load with the other players in the group, that's not a good thing.

I'll admit that I haven't been completely successful in this regard over the years. That's probably where I've learnt a few of my lessons, sometimes letting the wrong person into a group which has disrupted the existing equilibrium, letting players get distracted from the core story and losing the focus on the game and the group (or forcing players too carefully along a premeditated storyline, limiting their agency in the shared imagination space, and thus limiting the potential for their style of fun), or just misreading the room.

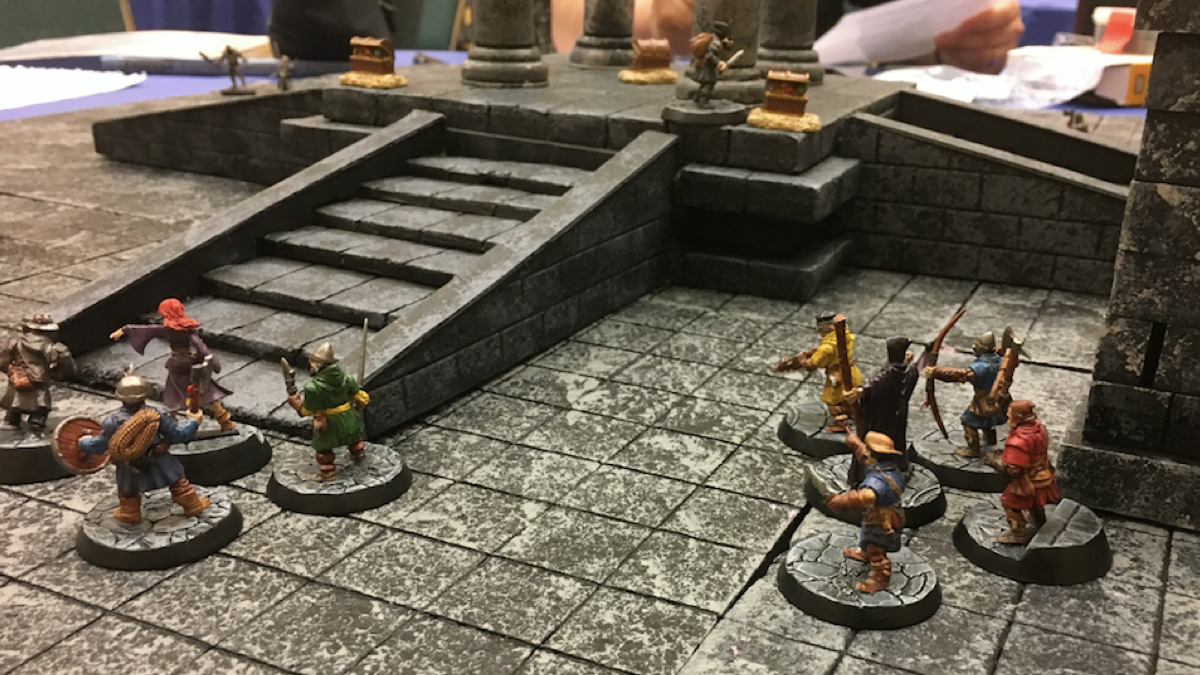

To take a specific example, the school lunchtime game club drew way too many players way too quickly. We started with about 12 players, I put a message in the daily notices, and that quickly reached over 30. I thought I could get away with running the club on two days a week, but 15 players a session was way too much, and overwhelming for both myself as the narrator and for many of the players. We grew too quickly without establishing what the group was about, how we intended to run things, and what the expectations of the community were. Players left because we didn't have focus, because everything was a bit disorganised, and because I didn't take the opportunity to properly explain to them how things were meant to work and how they would be a part of a wider imaginary space. This mean our diverse and interesting group degenerated...and it wasn't until I started splitting the group into smaller interconnected games that the group started to stabilise. That's when the group of students actually formed a community. Now it's just a case of drawing across a few new players between now and the end of the year, because more than half of players are going to move into their final year of high school and should focus more on their studies than on game sessions. The sport D&D groups are serving as a filtering operation to determine which players are likely to be suitable for the more exclusive lunchtime community that explores a range of different games.

Hopefully soon, I'll be able to talk about one of the other projects I was working on to help establish the community of play... but at the moment, things in that regard have been sealed.

Side Note: A lot of the stuff I've been mentioning here is echoed by other game designers... I've been alerted to this interesting post. It addresses stances (which I've discussed), and from another viewpoint considers ensuring the players are in board with the type of game that you're planning to run.

It clearly shows that there are certain types of players that wouldn't enjoy playing in the type of game that I often enjoy running, but that's a case of reading the table and providing an experience that does cater to the type of player being portrayed. I'd suggest that the first bit of the post describes a form of gamist pawn stance, it's not about interacting with the imagined story, but prefers to engage with mechanisms of play and aims toward winning encounters with die rolls. It's an interesting design choice to eliminate the descriptive element, and eliminates a chunk of the audience, while refining the play experience for the players it does keep.

.png)

Comments