Creating a Game (Part 2) - The Basics

Why create a game?

The counter question is "why not?"

For most of the duration of this blog's life, the fifth edition of D&D has been the dominant product inthe roleplaying market. It has been the basis of podcasts, it has seen a decent movie come out, it has been the centre of an ecosystem of third party products and has brought tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, arguably millions of nw players into the hobby.

As I said in my last post, D&D (particularly 5th edition) is so ubiquitous that one of the students in my my high school gaming club calls everythig else a homebrew. If I remember the context of his comment correctly, he specifically called Cyberpunk Red a "D&D homebrew".

Yeah, screw that.

D&D's market share has been a blessing and a curse. There are so many better games out there, and so many players who have left the hobby because D&D has not provided them with the experience they were expecting. There's a few reasons for this, and many of them have beenanalysed and debated over the past 20 odd years since the formalised critique and academic investigation of tabletop roleplaying games has been a thing.

I'm not going to go too far down that rabbit hole, because there are authors who've written books about the topic, and dedicated web forums where the concepts have been debated and picked to pieces (notably, The Forge, Storygames, Reddit posts like this, see also this article on Wikipedia). I'm just going to pick a couple of my pet hates, which have often led to problematic games, and look at the ways these issues have been addresed in games that aren't necessarily D&D.

(I'll note here that one of the biggest problems is that due to it's influence in the market, people shorthand the phrase "D&D" to mean all roleplaying games. "It's like sci-fi D&D... it's D&D but everyone plays werewolves... you oportray a role in an imaginary world, using dice, yeah, like D&D"... and that mentality has hamstrung a lot of games that offer a far richer play experience).

Don't get me wrong, I believe that D&D is a decent framework for play, but in most cases a good game happens in the gaps of the rules, it happens in spite of the hundreds of pages of rules and rulings, not because of them.

Case in point, I've been facilitating a multi-DM storyline over half a year as a variant on school sport. We ran a combat that lasted about 7 weeks, and we had to break out of the school sport routine to get it finished in this time. We ran regular sessions during most lunch breaks for that confrontation against one of the main villains of the setting. Hours and hours of play, just for one fight. Sure it furthered the storyline, but most of this had to happen behind the scenes... most of the 20+ players in the campaign have no idea how it all resolved. All they know is that something dramatic occurred. The D&D system just dragged it out, any heroic actions taken by characters just becamea part of the ongoing grind, and most things just came down to arbitrary chance rather than protagonistic decision making. In the end a single character choice, anda grand self-sacrifice did make the difference, and that's what roleplaying is about for me. But that's because I broke the rules of the game as written, I wanted that drama, but if I'd gone by the specifc textual rules everything would have come down to an initiative die roll...and we'd seen in game that the villain would have probably easily won that and led the seven weeks of combat to a wimpering anti-climax. Did I railroad the story? Did I engage GM fiat? Yeah, kind of, but it wasn't to give my villain the vicious conclusion he probably should have achieved, it was to give a solid choice to the characters again. D&D doesn't do that well, so I broke it and made drama in spite of the rules.

Let's look at a couple of issues I have with the way D&D and the way it works. If I was just retrofitting this one game, I might be producing a heartbreaker (arguably, D&D 5e is a heartbreaker with name brading on it)... but that's not what I'm aiming for.

Task resolution = aptitude level + random factor

A common idea in many RPGs is the idea that a character an pass or fail a task based on a combination of their skill factor and random factors beyond their control.

I'll paraphrase a couple of systems here...

White Wolf's Storyteller System does this is a pool of 10-sided dice, the better you are at a certain type of task, the more dice you get to roll. Each of the dice that rolls above a certain value (a 6 in the current version of the system) scores a success, but if you roll 1's they cancel out your successes. This gives a variable outcome that might stretch between an abysmal falure where bad things happen, a simple failure, a marginal success, or a momentous and legendary feat! A more difficult task might requre more successes, and an opponent might roll their own dice pool to eliminate your successes. Regardless of the outcome, the players and storyteller (that system's name for the DM/GM) are encouraged to work the result back into the story in some way. Players can declare any actions, and no matter what,they'll have a suitble die pool to accomplish it...it might be a small die pool indicatig a low likelihood of success, it might be a big dice pool with a good chance of success. Everything works the same way, and there are a variety of outcomes fom ever die result. (Here's a more complete look at the system)

At the simplest level you've got a 50/50 chance of performing a basic task, with a 10% chance each of getting something terrible (a 1) or something awesome (a 10). If you've got 2 dice, it's about a 70% chance of a regular success (noting that 1s cancel out successes), about a 5% chance of something terrible happening (more 1s than successes), and about an 8% chance of something awesome happening (more 10s than 1s). At three dice it's about an 80% chance of regular success, with the chance of terrible results being smaller than previous levels, and awesomeness being slightly more likely. This pattern continues.

For a more complex task (requiring 2 successes), you might take twice as long to even attempt it if you've only got one die With two dice, they both need to succeedso there's a 25% chance of success, 3 dice gives you the 50% chance... etc. The chances of goodness are scaled down, the chances of badness are scaled up.

The difference between success and failure is dramatically changed when going from unskilled to beginner levels of knowledge. However, as the dice pool grows, the chances of succeeding don't see as much difference from level to level. At higher levels it's less about the chance of success, and more about the chances of gaining multiple successes and succeeding with style. That's all a part of the game.

Powered by the Apocalypse games have a few varieties now, but the basic system is basically rolling 2 six-sided dice and adding the result to a modifier between -2 and +2. A roll of 6 or less is a failure. A roll of 7 to 9 is a mixed success, something good might happen at a cost. A roll of 10 or higher is a complete success. The catch here is that every character is designed by looking at stereotypes and genre archetypes. You can only negotiate with someone if you're a trader and that's your role in the story. You can only fix cars if you're the story's designated mechanic. In most cases, player have a choice about how things go right or wrong in their actions, and this adds a level of protagonism beyond the mere choice of whether or not the attempt will be made. The specifc outcomes of certain types of tasks are written into the character sheet in a playbook, and the playbook serves a lot of the functions of a players guide and a character sheet. It keeps characters in their lane, but in many variations of the system, characters can learn things from one another.

A standard task with no modifiers (if the story has put you in an appropriate situation to attempt it, and if you've got the right moves) has a 15 in 36 (42%) chance of just failing, but this isn't a stopin the flow of things. Instead it often means that the narrative shifts in a way you didn't account for, or you suffer some kind of penalty. Nothing gives a 'null' result. There is similarly a 15 in 36 (42%) chance of a mixed result, or a success with sacrifice (depending on the situation, and the specific move used). The remaiing chances, 6 in 36 (or 1 in 6, 16%), are a full success.

If a character is rolling with a +1 to their roll, the chance of a failure drops to 10 in 36 (27%), the chance of a mixed result shifts to 16 in 36 (44%), and the chance of a full success also becomes 10 i 36 (27%). Further increases in modifier expand the chances of getting a full success and reduce the chances of getting a full failure, while decreases in modifier do the reverse. But the spirit of the game lies in the interesting effects of mixed results and successes with sacrifice... that's what the system is aimed towards, and that is generally the most common result of a dice outcome.

There aren't really the opportunities to show off success at a higher degree of style and flair, there are certain moves that make characters shine in certain types of task, but "heroic awesomeness" isn't really what the game engine was designed to do. It's a system that facilitates drama and choices.

D&D has a few systems, it has always had a few systems. However at the essence of most editions since 3rd there has been a roll of a 20-sided die, modified by a skill factor. As a fundamental system, there'snothing wrong with this, as long as you understand where the idea of the system is coming from and where it is aiming towards (intentionally or otherwise). I think I've written about it previously on the blog, I know I've explained it to various people over the years, but my biggest issue with D&D is the way the game is presented versus the way it is mechanically structured. The core system rolls a 20 sided die, then adds a modifier which is typically between 0 and 10. The 5e version of the game specifically stripped back the modifiers for reasons I'll get into with the paragraphs below. This basically means two-thirds of your outcome is based on random chance, and only one third on the actual abilities of the character. In a world of chaos and comedy, that's fine (and due to the system it's often how successful games work when they lean into the potential for the ludicrous)...but when when many of the supplements are presented as heroic stories or tonally serious, there actually isn;t much opportunity for characters to make a difference in a world where chaos has more influence than skill or knowledge.

An easy task has a difficulty of 10, medium 15, hard 20, extremely hard 25, virtually impossible 30. At low levels, a character probably has modifiers between 0 and +5 (yes, there will be outliers, especially when players maximise their abilities in certain fields). A 0 modifier renders those hard tasks impossible to achieve. A carefully written starting character (with +5) has a limited chance of achieving "extremely hard" tasks...however, they have better chance of failing an easy task, and still have a 50/50 chance of failing a medium task. This is not a recipe for heroics, but can make for fun stories of survival against the odds.

As a follow up, the base rules of D&D bring everything to a standstill with a failed roll. You either move forward in the story with a pass, or need to look for another option if there's a fail. There's no nuance of degrees of success, and there's no complexity of success with a sacrifice...unless you house rule it, and then you're not really playing rules as written. To make thing worse, you might then apply saving throws which determine whether a character suffers as a result of an event. There could be a whole heap of die rolling, and counter die rolling with no effective change in the story or the status of the characters.

Earlier verions of the game had various systems and subsystems that have basically been streamlined out of the game, so I won't get started on that rant. Echoes of that legacy play out in the way combat is handled differently from magic, and both are handled differently to most other tasks and skills.

Basic Role Playing (BRP) is the core system at the heart of games like Call of Cthulhu. It runs off percentages, so you instantly know what your chances are in a given task. BRP is a game system from the 80s, and while it has generally been stable for over 40 years, it's age is starting to show. To determine your chances at a task, the GM picks a difficulty (this could be from -50 to 100), and the players adds their skill rating to it. If the figure is below 0, there's no chance of the action succeeding, if it's over 100, then it's a guaranteed success. Between those results is apercentage chance of pass or fail. Except for the fact that it uses percentages, it still has the old pass/fail artefact similar to D&D, and a combat system that ends up adding layers of complexity, tactical shenanigans, and motions toward "realism" which really only amount to slowness in the procedure.

Where does that leave things for a new game?

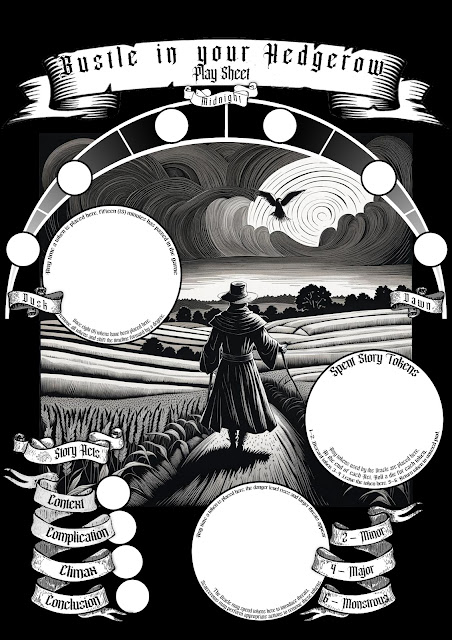

My initial thoughts for "Bustle in your Hegderow" were to base it on my previous game "FUBAR", which uses a variant on the system called Otherkind Dice. I have a love for this system and the elegant simplicity that can be applied to a range of scenarios and tasks.

The FUBAR system works on three outcomes for every task: "success", "sacrifice", and "story".

Success - How well did you do?

Sacrifice - What did you give up in the attempt?

Story - What influece does this have on the narrative?

For simplicity (and to match the original Otherkind format), everything in FUBAR runs on a six sided die.

Success

1-2: Fail (the chance to succeed has passed)

3-4: Nearly there (someone else may try, or you may try again)

5-6: Success

Sacrifice

1-2: Major Sacrifice (two problems have emerged)

3-4: Minor Sacrifice (one problem has emerged)

5-6: No Sacrifice

Story

1-2: The GM/Narrator gets to describe the success and sacrifice.

3-4: The GM/Narrator describes success or sacrifice, player describes the other

5-6: The player describes the success and sacrifice

As straight die rolls go, there is a tendency on average for things to get worse with every die roll. However, players get to allocate their results after they have rolled, and they have a few advantages at their disposal. Firstly, they get extra dice if they have advantages that might help the situation, and the lowest reults may be dropped. Secondly, they might voluntarily leave the descriptions of events in the hands of the GM/Narrator, leaving their better dice for higher success outcomes. The system is designed to draw its modifiers directly from the events in the story, and then filter reults straight back into the story, in a cycle of play.

FUBAR is a game about desperation, trying to make a difference in a world where the odds are stacked against you, and using a specific skill set to enact vegeance (or bring justice). It's systems feed those ideas, and it works as a fit for where I had "Bustle" heading. There's also some fun token movement though the game that can be played in various ways to add drama.

The only difference I immediately wanted to make was to link seasons, weather, and faerie magic into the fundamental levels of the game. So I'm switching from standard six-sided dice to standard playing cards. 52 cards = 52 weeks of the year. 4 suits = 4 seasons. 2 jokers = 2 courts of faeries (seelie and unseelie, separate from the cycle governing the natural world). Just as the "Powered by the Apocalypse" games thrive in the middle ground where decisions are made, I'm expanding the middle grund for each of the result categories (this accounts for the odd number of card ranks).

A-4: Lowest result

5-9: Mid result

10-K: High result

We can play with suits and the way the cards are shuffled as a part of the game mechanisms later. That'll do for the moment. More to come soon...

.png)

Comments

That makes the breakdown...

2,3,4,5 = Low result

6,7,8,9,10 = Mid result

J,Q,K,A = High result

The shift to cards allows the potential for interesting things happening to the task outcome based on pairs, triples, four-of-a-kind, flushes, and similar effects found in poker and other games too.

There's more to the system based on the partial design I'd come up with last year, but we'll get to those bits soon.